Pasture, people, power growth

Tough times hit Mick and Kirsten O’Connor’s equity growth plans at a perilous time, but they powered through thanks to great systems and supportive farm owners who want their farms to grow farmers too. Words Anne Lee, Photos Holly Lee.

Mick and Kirsten O’Connor’s farm business name is a not-so-subtle clue to the couple’s farming ethos.

Grass Gobblers Ltd is exactly as it sounds, a grass producing machine where the aim of the game is to harvest all the high-quality pasture the farm can grow and turn it into nutritious milk using 1000 well-primed, grass gobbling cows.

Why? Because the pasture-based system is the best way they’ve seen to meet their family goals. It creates profit, builds equity and the simplicity allows flexibility. That ticks a lot of boxes when it comes to their family goals of being present for their children and being able to give them the best opportunities they can.

They frequently refer to their farm team as part of their extended family and want to keep the progression stairway moving for them, as it did for the couple, so they can create opportunities for team members to step on to the ladder also.

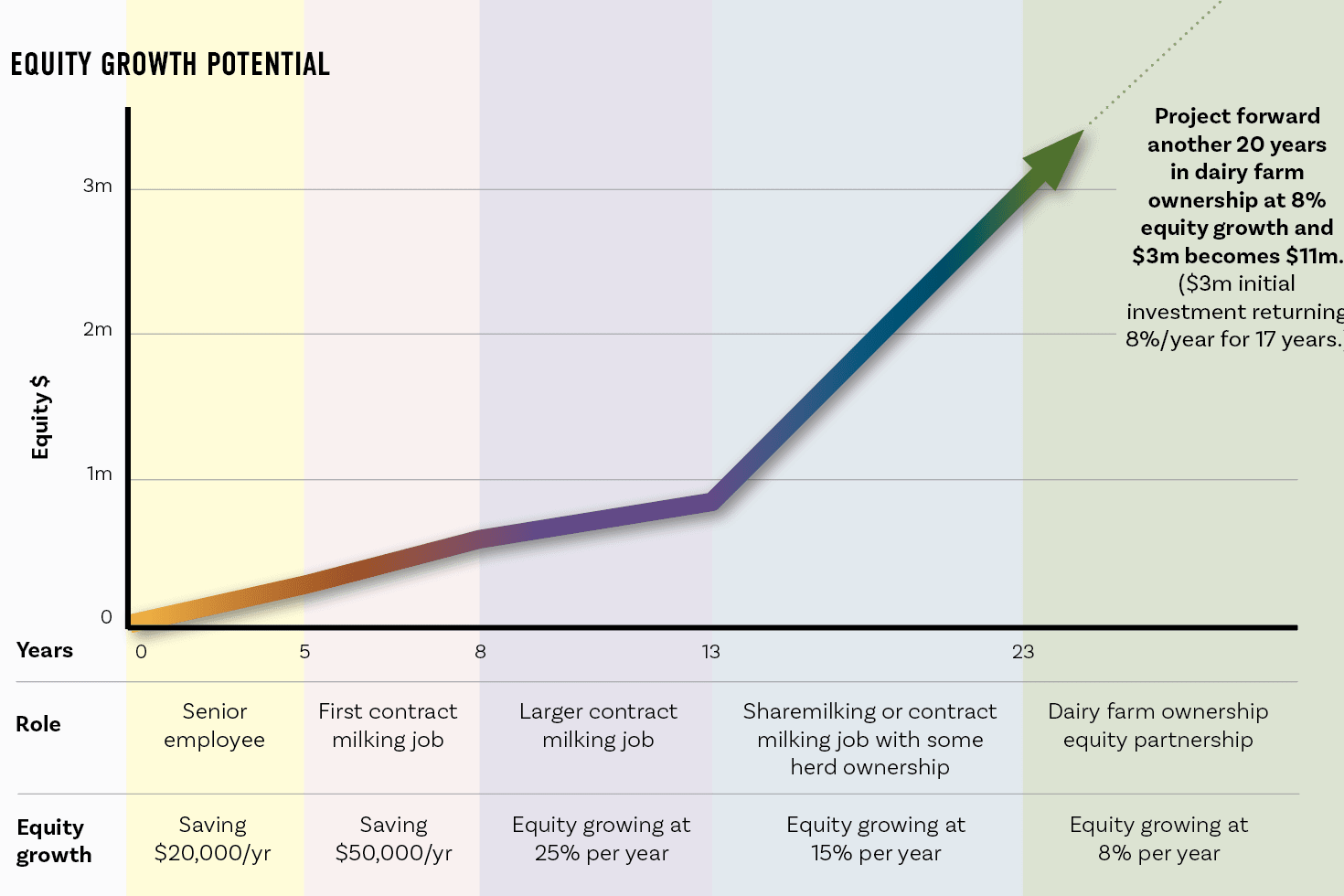

Mick and Kirsten have used the time-honoured and well-trodden pathways dairy has afforded young, go-ahead farmers for decades, making the most of opportunities in contract milking, followed by lower order and then herd owning sharemilking.

A combination of rearing and purchasing stock and then leasing them back to the farming business has been a big part of their steep equity growth.

But so too has the relationship they built with their farm owners through their proven work ethic and shared farming ethos.

They’ve worked for and with Dairy Holdings (DH) for more than a decade, with the company’s farm management structures providing flexibility, opportunity and backing as it walks the talk on its company tag line “Farms that grow farmers”.

“When you’ve been through a downturn, you know it’s going to come again eventually. It’s like a rubber band, it will come. We can’t control the payout but we can control our costs.” – Mick O’Connor, Canterbury

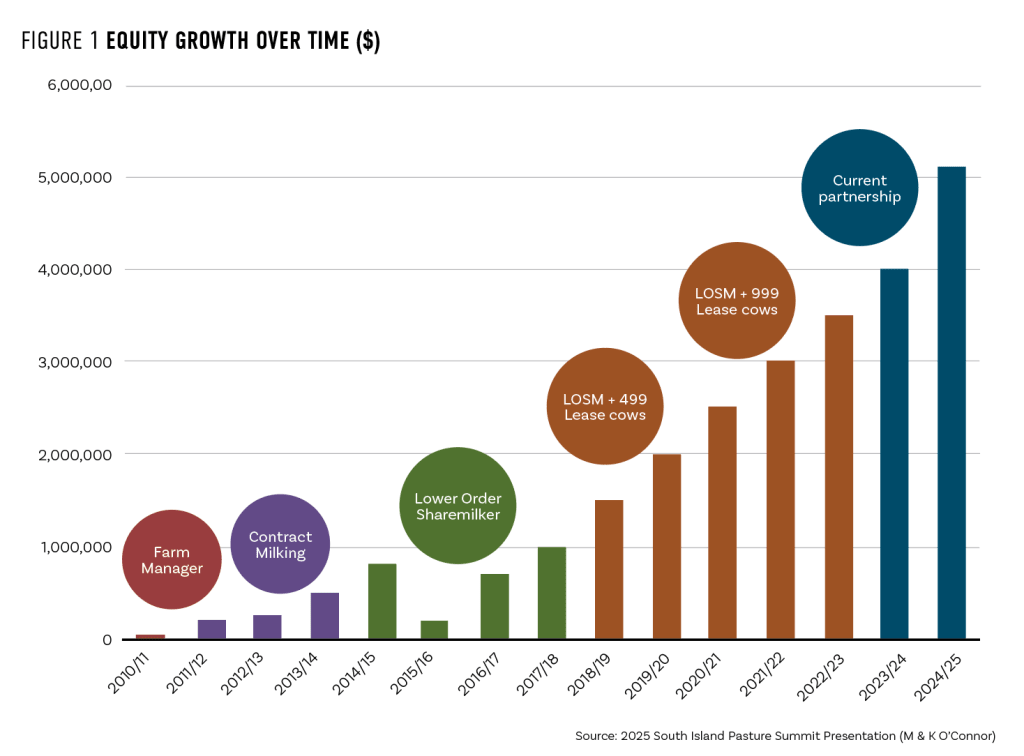

The couple explained their equity growth story at the South Island summer Pasture Summit, sharing that they experienced what were perilously tight times early in their farm business career.

They had saved hard and, through a combination of rearing youngstock and purchasing them from DH, had built up their own cow numbers to 200. They’d bought another 300 to take on the lower order sharemilking opportunity so they owned half the 1000-cow herd they were running.

They earned 39% of the milk cheque and paid a share of the costs. With an $8.40/kg MS payout in 2013/14 giving them confidence in their first season of lower order sharemilking, they bought another 500 cows so they could step up again and own the whole herd.

But the milk price crashed to $4.40/kg MS in 2014/15 and then took another nosedive to $3.90 the following season.

“That’s where we probably learned our biggest lessons – making milk costs money and we had to understand whether it was marginal milk through the back end of the season. Were we actually making money from producing another (milk) solid or was it actually better to dry the cows off and not make that milk?” Mick says.

They leaned on others who had been through downturns before, kept their heads down and ploughed on farming. “Unless the bank was going to step in and sell us up, we weren’t giving up. We would have been better off going back managing but we believed our farm system was the way to ride it out,” he says.

They had cash saved that was earmarked for buying cows but they drew on that to prop themselves up.

“The experience hammered home a few disciplines,” Kirsten says.

“It sounds cheesy but keeping a strict personal budget and understanding where we were spending every dollar really mattered. Sometimes it might look like a food diary but it’s really important to be aware of those $10 and $20 small amounts.

“Those years really helped us hone our system and understand where our dollar was best spent. The opportunity (pictured in orange on figure one) came off the back of really understanding our system, our numbers and having confidence in that system,” she says.

DH had confidence in them too, and through those tough payout years, contract percentages adjusted so they received a greater proportion of the milk cheque.

“They do that because they recognise that as payout drops, sharemilkers shoulder a larger proportion of the costs in their businesses.

“The contracts are variable so they’re fair to each party. When the payout is high, the percentage will drop back a bit, but when it’s at very low levels it ramps up because the company genuinely wants people to get through and be able to grow.

“They saw we were in a tough position and while we were in that low equity phase they backed us so we could bounce back up through that as fast as we could and continue to grow,” Mick says.

And bounce back they did, not only due to the contract but also thanks to their driven focus on disciplined budgeting, hard work and sticking to their tried and true pasture-based plan. By 2018/19 they added another 499 cows to their name which they then leased back to DH. Four seasons later and that number had doubled.

Mick says DH has about 59,000 cows across its farms. Of those, about 16,500 are owned by contract milkers, sharemilkers and office staff.

“Everyone has the same opportunity to own youngstock. The company recognises it can help people grow their equity above what they earn in wages, no matter what their role is within the business,” he says.

For Mick and Kirsten, the opportunity to take the next big leap came in 2023 when they bought the 260ha Burnham dairy farm with two other equity partners. Each shareholding entity has an equal shareholding.

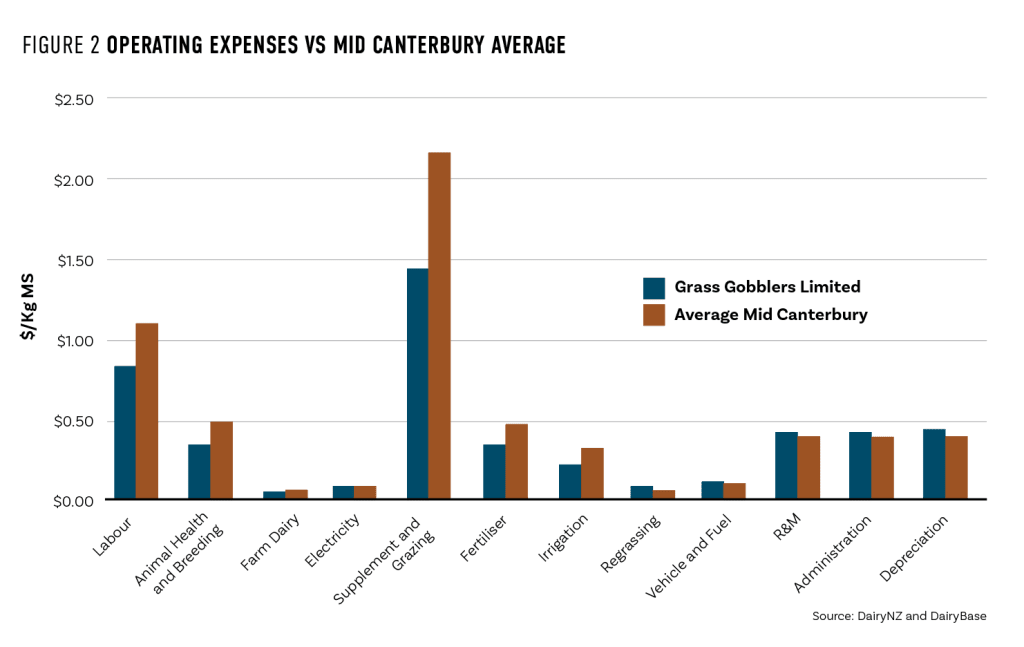

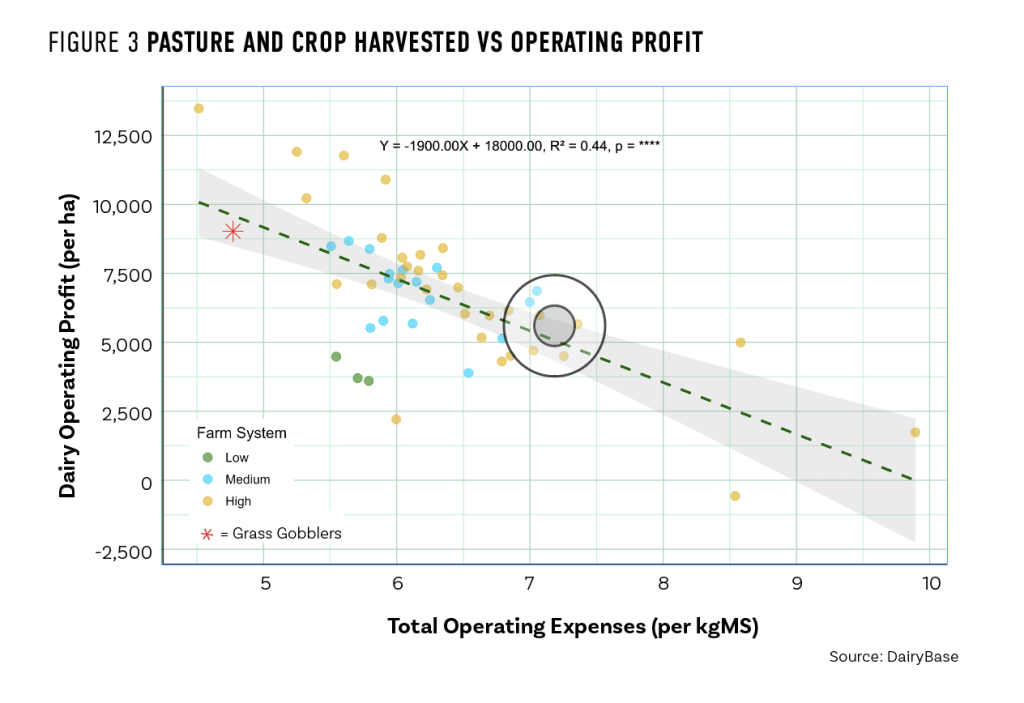

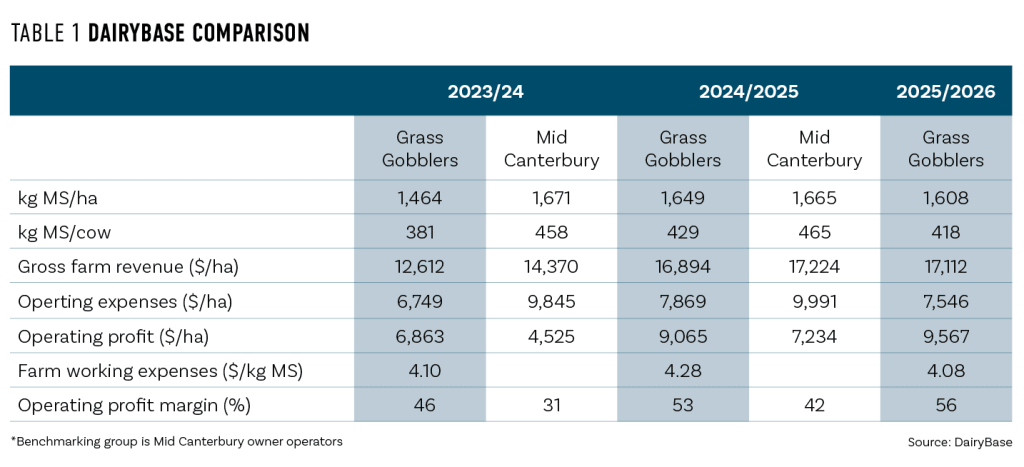

The couple held onto those early lessons throughout their sharemilking career and took them through to farm ownership so their operating expenses, at $4.77/kg MS, were amongst the lowest in a Mid-Canterbury benchmarking group for the 2024/25 season, enabling them to produce an operating profit of $9065/ha.

Comparing them with other Mid-Canterbury farms in DairyBase, where the average operating profit was $7234/ha last season, it’s apparent the main difference is significantly lower costs rather than a higher income. (see Table one)

One of the criticisms of lower input systems is they leave profit on the table through high payout periods because they haven’t chased production, but Mick says he was happy to see that benchmarking analysis showed the farm still sat amongst the top performers for profit last season too.

“There’s no finger in the wind. Every month we need to know where our money has gone.” – Kirsten O’Connor, Canterbury

“When you’ve been through a downturn, you know it’s going to come again eventually. It’s like a rubber band, it will come. We can’t control the payout but we can control our costs.

“Looking at the benchmarking we’ve got a bit of insight into how good our system actually performs in a higher payout and we know it’s robust at a low one,” he says.

As well as previously working within the DH system as a contract milker and sharemilker, Mick also works as a supervisor – a role he’s continued in after taking on farm ownership.

Kirsten’s career has been in banking and she has been integral to managing their farm business finances.

Every month she reviews what’s been spent with what was budgeted and once their milk payment arrives, she knows exactly what they’re paying off in principle.

“So we’re ready to send that email off to the bank manager because that’s really important to us. There’s no finger in the wind. Every month we need to know where our money has gone,” Kirsten says.

Three years ago the couple carried out a DairyNZ full farm assessment which helped them fully articulate their goals and values.

“We took away some real gems from that and identified four family values – family time, integrity and loyalty, achievement and economic security.

“So when we make decisions around our family, our business, we ask the question – will it take us closer to our goals and values or further away?” Kirsten says.

They have six key messages for those starting out their progression journey.

- Be patient – building equity and skills takes time.

- Upskill continuously – learn your craft. Learn grazing, budgeting and business management.

- Seek an employer who is going to take the time to upskill you.

- Understand your numbers – don’t rely solely on professionals.

- Keep it simple – fewer decisions lead to better decisions.

- Sacrifice – getting to farm ownership has never been easy.

Mick sums up their farming philosophy as one that is simple, repeatable and can work successfully if he’s off-farm.

“We can never control the milk price but we can control costs. That’s a big one for us. The fewer things we have in our system, the fewer decisions that have to be made, the easier it is to get things right and the more enjoyable it is for our people.

“There’s no finger in the wind. Every month we need to know where our money has gone.” – Kirsten O’Connor, Canterbury

“If you’re putting lots more things into the system, it gets harder to control costs – there’s just more of them and some of them are loaded into the future so you can’t get them out easily,” he says.

The key management priorities are grass growth, pasture harvested, grazing management and farm walks to guide decisions.

Focusing on feeding the pasture wedge to maintain target average pasture covers is the goal, not chasing production.

The Grass Gobbler system

- Farm walks every week are non-negotiable

- Ensure residuals are met all year round

- Use spring rotation planner

- Autumn management plan

- Match pasture supply and herd demand. Utilise high cover in spring and then destock in the autumn

- Meet key, pre-determined average pasture cover targets

- Bring the team along on the journey.

Autumn is the prime time to set up for the following season. They use an early culling tactic to ramp down feed demand so it matches slowing supply. That reduces the need for bought-in feed and is a major aspect of their lower cost, pasture-focused system.

Final pregnancy testing is completed in February and culling begins in March when round length is pushed out to 40 days from the 30-day rounds through January and February.

“All culls are gone by the end of March. The added bonus is there’s plenty of space at the meat works then and prices can also be higher,” Mick says.

Early culling helps build average pasture cover to 2600-2700kg drymatter DM/ha by the end of March and as growth rates slow down, round length pushes out further to sit at 50 days by the end of April. Average pasture covers continue to fall but importantly demand is still met. By mid-May average pasture cover is at about 2000kg DM/ha and, with continued careful monitoring and management, the farm team ensures they meet the June 1, non-negotiable target of 2100kg DM/ha.

While there’s a small once-a-day (OAD) milking herd throughout the season for any lighter or sick cows, the team doesn’t use the tactic through the autumn, instead drying off lighter cows.

Cows winter off-farm on a neighbour’s property on fodder beet, kale and straw.

By spring, pasture covers have built to about 2900kg DM/ha. The team strictly follows the spring rotation planner to ensure cows are well fed, every blade of grass is utilised and feed supply and demand is carefully matched. Pasture is allocated to calved cows on a square metre per cow basis which increases for each cow based on days since calving.

“A big focus for us around spring time is pasture management and protecting soils and pasture. Our team is awesome at that. We graze like we’re in Southland, starting at the back of the paddock, using portable troughs and back-fencing every day as we work our way to the front.

“We can never control the milk price but we can control costs. That’s a big one for us. The fewer things we have in our system, the fewer decisions that have to be made, the easier it is to get things right and the more enjoyable it is for our people.” – Mick O’Connor, Canterbury

“The team manages multiple paddocks at once and if it gets wet, they put up a laneway that’s wide enough for cows only rather than a vehicle, and then we can just drill along that thin strip to repair it,” Mick says.

“They’re very quick at shifting cows off onto paddocks earmarked for renewal too,” he says.

Hitting residuals in spring is an absolute must to protect feed quality going into subsequent rounds.

Farm walks are a task Mick takes on himself at least weekly. During high growth periods or when temperatures are fluctuating widely, he’ll walk the farm every four days. Pasture covers are measured by eye and put into AgriNet Grass software.

“Farm walks are my main job on the farm. All our feed decisions are to make sure we stay on track around our average pasture cover.”

He sense-checks his measurements.

“It’s not just about putting down numbers. I’m looking at residuals and calibrating my eye with what the cows are telling me.

“Balance date is usually about October 1 and as they contemplate speeding up the round, they’re looking very closely at both temperature and growth rates,” Mick says.

“We look at what the information is telling us now and we make decisions on that rather than on what we think might happen. It means we have to look at it really closely during those times when growth rates are picking up and changing. A week can be too long between farm walks and if you let it get ahead of you by just a few days, you can be in trouble with quality.

“We’ll fluctuate from 23 to 25 days as growth rates pick up and anything that gets over 3200kg DM/ha we’ll put through a mower and into a bale. We don’t always get it 100% right – last year we dropped to 21 days, made balage and then growth rates dropped and we ended up feeding it straight back out.

“We will use supplement if we really have to – we’re not allergic to it. It’s more likely to be around November if we come into a bit of a pinch.

“We feed about 50-60kg DM/cow of bought-in silage. It’s simple to feed and our feed decisions are around feeding the wedge. So if we don’t have the pasture cover, we’ll lengthen the round out – go to 30 days and put a heap of feed in at once so we push pasture cover up quickly, not just slowly chip away at it.

“It means we’re planned and calculated about it to get the average pasture cover back up quickly,” he says.

They take paddocks out for renovation using a diploid ryegrass and white clover mix, but they’re reviewing their approach to establishing new pastures.

“We used to view pasture as a 17 or 18 or 20 tonne (per hectare) crop, now we’re thinking about it as a 200t/ha crop, given we want it to be lasting 10 years.

“That means we need to take more care through that establishment phase – make sure we’re dealing with the weeds and we’re drilling it so we get a dense sward. It’s something we’re looking at,” he says.

One of the first things Mick and Kirsten did after taking over the farm was soil test every paddock and carry out a pasture assessment with Fonterra, scoring every paddock, looking at factors such as pasture species and weeds.

That revealed a wide range in phosphorous levels with some Olsen P levels down at 14 and 15 and others up to 45.

“Quite a bit of corrective fert went on to start sorting that out. We’re aiming for Olsen P’s between 25 and 35 and a pH of six,” Mick says.

The farm walk data and paddock scoring information has then informed their pasture renovation plans.

Urea is used to boost pasture production, with a simplified approach of applying it to half the farm every two to three weeks, selecting paddocks based on what’s just been or is about to be grazed.

Non-effluent areas receive six applications, with a season total of up to 190kg N/ha. The timings mean none is applied in October or January and the last application goes on in March.

Effluent areas receive three applications to give a total of about 100kg N/ha with timings in mid-August, late-September and March.