Profitable pasture

Creating pastures to sustain a profitable farm system has been central to the Armstrong family’s expansion and improvement of their Taranaki operation over the past three generations. Now as the fourth generation take on their roles and the Newells take on contract milking the dairy farms, pasture performance remains a top priority. Words & Photos Anne Lee.

Nearly 100 years on from the purchase of the original parcel of 80ha, the Armstrong family’s forebears would barely recognise their farm and surrounding area that now forms the family’s more than 600ha enterprise.

Gone are the rush covered swamps and tussock encroached paddocks. The varicose outcrops of rocky, remnant lahars have been laboriously levelled over three successive generations so that now the significantly greater area is primarily lush productive pasture.

Ian Armstrong’s mother, Olive, was daughter to the family’s original Te Kiri settlers, Oliver and Lizzy Dowman. He doesn’t know how many cows they brought from their sharemilking job when they made that first land purchase in the early 1930’s, but by 1945 they had 87 cows – “An indication of just how rough the land was,” he says.

The volcanic soils hold phosphate tightly and a solid iron pan impedes drainage, so it’s taken decades to tame the land, initially by manually picking up stones, digging through the pan and laying many kilometres of painstakingly, handmade, stone and then later tile and plastic drains. Even then, the iron creates a ferric oxide which can clog the drains, so they require cleaning out by water blasting at strategically created openings.

In 1979 Ian was working for the then Department of Māori Affairs as a field officer carrying out farm advisory and valuation while Judith, a maths and physics university graduate, was finishing her teaching diploma. They were about to embark on two years working in Tanzania on a government aid project teaching dairy farming when a 96ha block near the family farm came up for sale.

They bought it and Ian’s father oversaw the management of the 134-cow property for two years until they returned from Africa.

Development work was also sorely needed on this farm and Judith remembers on their return, driving a tractor with their infant daughter in a front pack, while others walked behind picking up stones. In 1986 Ian’s father died unexpectedly so he and Judith assumed full management of both operations – then 208ha.

“The thing with farm plans and budgets is that in farming, things seldom go exactly to plan, but by measuring against it – budget versus actual – on all the KPI’s we measure here, any variance raises a flag so you can ask why. – Daniel Newell, Taranaki

Over the next 20 years they worked hard to carry out further development and added additional neighbouring blocks – one of 57ha in 1988 and another, 132ha in 2000. The latest addition was the biggest purchase, with 296ha bought that bordered the far western end of the property. It too needed extensive development of lahar outcrops with the block also including an area of West Coast lease land.

There are still rocks across the farms in sections and drainage continues to be an ongoing issue, but they achieve a pasture harvested figure of 13-14t drymatter (DM)/ha.

Ian and Judith’s son-in-law, Jonny Wright, is the operations manager, overseeing the two dairy farms and large-scale support block that make up AME Farms.

A mechanical engineer who has specialised in water treatment infrastructure, the Australian born Jonny took up his current role seven years ago, about two years after he and his wife Paula, also an engineer, returned to Taranaki.

“It’s the dream job I didn’t know existed,” Jonny says.

Paula’s sister Ellen, a management accountant based in Wellington, has also taken on a role in the business, in governance and finance, managing compliance and as property manager for the farm’s eight houses.

Contract milkers Daniel and Monique Newell are in their eighth season with the Armstrongs and work across both the larger, 320ha, 945-cow Eltham Rd farm and the adjacent, 75ha Waiteika Rd farm which milks 230 cows. Drystock manager Jacob Hancock looks after the replacements and bulls on the 220ha supporting drystock block.

“By June 1 it’s about measuring actuals against the plan through FARMAX so they can see how it’s going to affect cashflow through the season.” – Grant Leigh, Green North Face consultancy

The current structure, involving Jonny and Ellen, was set up to enable Ian and Judith to step back from day to day matters as part of a well-managed succession planning process but maintain family oversight and involvement.

The transition is enabling Ian and Judith to focus more on governance.

Farm consultants Grant Leigh and Alicia Riley have worked with the Armstrongs for several years and are part of the management team, with Grant advising on the Eltham Road and drystock farms and Alicia on the Waiteika Road property.

Everyone knows the part they play in the organisation, with each a valuable cog bringing their own strengths.

They’re also all aligned on the principles of a pasture-first, low cost, profitable system to enable the wider goals for the business.

To achieve that, Grant and Jonny meet early in the year and use FARMAX to set up a farm plan for the following season. Stocking rate, feed inputs, milk and stock income are all discussed and budgets drawn up.

“We look at what we might change from the current season and once we’ve set the plan and the budget they (Jonny and Ellen) can go through and cashflow it out.

“By June 1 it’s about measuring actuals against the plan through FARMAX so they can see how it’s going to affect cashflow through the season,” Grant says.

Feed budgets and winter feed budgets are drawn up and importantly also monitored.

“The great thing here is that they actually follow the plans, monitor what’s going on and follow the systems and principles that are pretty simple. A lot of other people say they’re going to do it but they

don’t,” Grant says.

The results of following those simple systems speak for themselves.

The family shared their system and results at the North Island Pasture Summit in December.

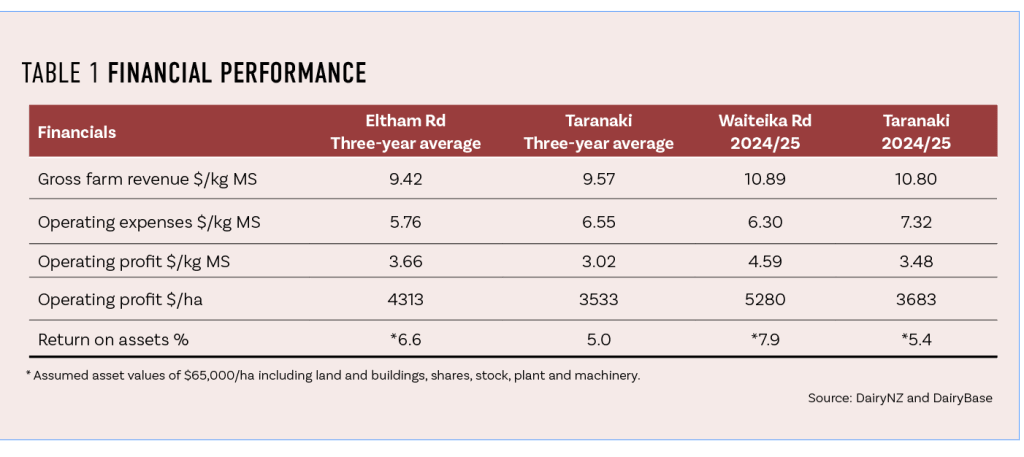

Operating profit is consistently above the Taranaki three-year average. DairyNZ analysis of their financials in Table 1, which combined contract milking and farm owner figures, shows that it’s not a higher gross farm revenue driving the performance but a lower cost structure, due largely to lower supplement costs.

Labour costs are above average with a high priority placed on the value of people by both the Armstrongs and the Newells.

DairyNZ senior business specialist, Paul Bird, pointed out at the field day that while 64c/kg milksolids (MS) difference in operating profit might look small, when multiplied out over the whole enterprise over a three-year period it amounts to about $700,000 of additional cash.

“It might look like a few cents, but multiply the resulting extra cash out over 10-20 years and it’s in the millions of dollars,” Paul says.

“In terms of our system, we’re aiming for simple, low cost and trying to be flexible and repeatable season after season,” Jonny says.

Two seasons ago, Jonny and Ellen carried out a “deep dive” into the business costs. It highlighted the expense of the cropping system they were running given variable yields, likely because of the soils.

Based on the analysis, they pulled the crops – turnips, kale and some maize – out of the system and focused even more strongly on pasture.

Daniel and Monique are tasked with achieving results from the pasture-first system and do so with their team of five full-time staff through diligently sticking to tried and true systems and focused communication.

They use a 24-hour grazing system with cows going into their new paddock after afternoon milking.

“That means there’s no shifting cows at night, we’re coming in the next morning and I’ll get feedback from the guys on what the grass situation is. It gives us options where we can take action then – do we need to shift cows earlier or not?” Daniel says.

If cows aren’t likely to hit residual, the aim is to still shift the main herd on to the next paddock but another group of cows is likely to be used to clean up. Daniel runs three herds through the bulk of the season.

Mowing before or after grazing isn’t used as a tool to maintain pasture quality. Many paddocks have sections that aren’t mowable because of rocks and it’s not a favoured practice because of cost.

Planned start of calving is August 1 and by day 10 they can be well past half way. It’s fast and busy for everyone. They have up to eight herds through calving.

“There’s lots of moving parts and lots going on, so it’s really important that we have the cow shed humming so I can make sure that the grass is getting fed properly,” says Daniel.

They have pre-prepared plans and staff are well drilled on what they must do and what’s expected. The whiteboard in the farm dairy serves as a detailed form of communication along with WhatsApp groups.

“The spring rotation planner is super simple and through August we are super strict with that.

“I have to try and make sure my guys understand some basic stuff – square meters per cow, setting fences in the right spots. We list all eight mobs on the whiteboard, which fences go where,” he says.

Throughout the farm business, people are a top priority and team culture is a real focus for Daniel and Monique. One on one discussions build understanding of where staff are at and what their goals are, so developing their skills and ensuring they’re working to their strengths helps in creating a good team culture.

“I trust our guys are doing the best they can all the time,” Daniel says.

He’s aiming to nail 90% of the plan every time rather than perfection, which just isn’t reality, particularly in larger teams during peak work periods. “Sweating the small stuff when the heat is on, just isn’t worth it – the key is knowing the difference between the small stuff and the non-negotiables,” he says.

The farm team uses technology such as Harvest.com, installed by the Armstrongs. Soil moisture and temperature data help in preparing and managing pasture grazing plans. Data from the C-Dax tow behind pasture meter and more recently AIMER, smart phone-based pasture measurement and feed planning technology, also play a key role in pasture management.Residuals are the main topic of conversation between staff and Daniel each morning. Everyone is aware of just how important it is to get them right in terms of setting up paddocks for the following grazing.

“It goes back to me making sure my guys get it right, that they have a plan in place and we can set up August to make September easy and then set up September to make October easier and so on – the residuals are definitely crucial to getting that right,” Dainiel says.

“Daniel is connected to the grass through his team, so 90% of the time the right decisions are being made with residual. And that’s the thing that’s hard to do at scale when you have multiple people looking at pasture, but they’ve developed a system to be able to do that,” Grant says.

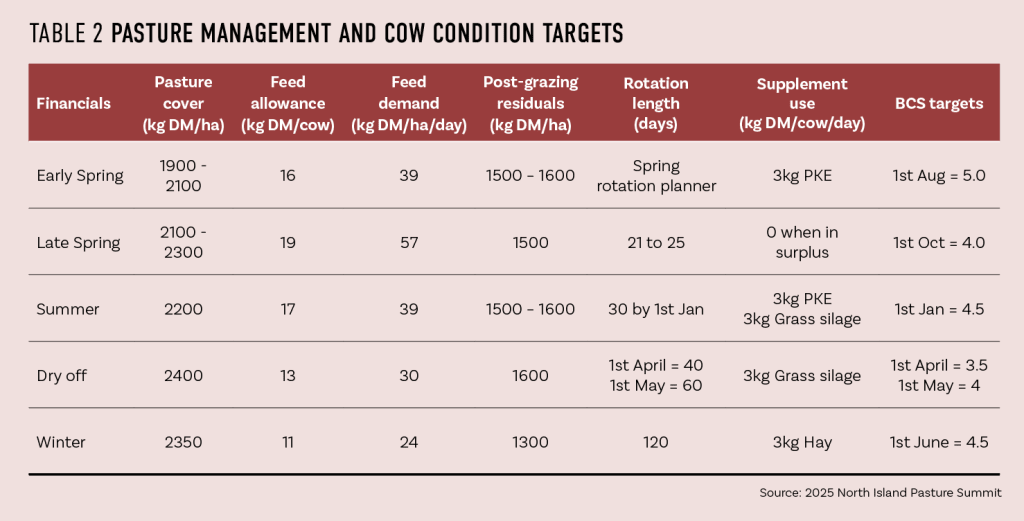

For early spring it’s round length and feed quality as a key focus and through October the aim is to go no faster than a 21-day round. Making quick, smaller cuts of silage helps manage feed surpluses while reducing the risk.

“We won’t really have much more than 15% out for silage at any one time. Not all of the farm is mowable, so I’m constantly checking that the hill paddocks are grazed down well and we might do slightly shorter grazings on the trickier paddocks.

“It might look like a few cents, but multiply the resulting extra cash out over 10-20 years and it’s in the millions of dollars.” – Paul Bird, DairyNZ

“By October, we have three milking mobs and I might have all the old cows on the top side of the farm and all the young cows on the bottom side, but then I have a third milking mob with about 150 cows that are really close to the shed but that also gives me another grazing tool,” he says.

Supplement, mainly palm kernel, is fed in troughs through spring to ensure cows are fully fed, but as soon as the farm reaches balance date, the supplement is pulled out.

Summer is often about survival through what is commonly a dry period because a good autumn flush is “fairly reliable”, both Ian and Daniel say.

Silage and palm kernel are used to fill the feed deficit and round length is typically about 30 days by January 1.

The aim is to keep as many cows milking twice-a-day as possible, knowing autumn growth is coming but through April and into May cows can be dried off based on body condition scores and calving dates.

Round length is out to 40 days by April 1 and 60 days by May 1 with a 2400kg DM/ha cover targeted for June 1.

Winter feed budgets are done early with a proportion of the cows wintered on the farm’s support block

on grass.

“The thing with farm plans and budgets is that in farming, things seldom go exactly to plan, but by measuring against it – budget versus actual – on all the KPI’s we measure here, any variance raises a flag so you can ask why.

“If growth rates are high but your average cover’s low – then what’s gone wrong? It’s a flag. If body condition is too low and we’ve had great growth – what’s happened?

“We look at the actual versus budget and we talk about it. We do the numbers and we talk about what we’re going to do, how we’re going to adjust so it’s about understanding what’s happening in reality and being flexible, acting on that knowledge,” says Daniel.

The whole farm team – including Ian and Judith, Jonny, Ellen, Daniel and Monique, Grant, Alicia and other farm staff, are all aligned with the data, planning and reviewing, and acting on that review is fundamental to achieving high performance.

Mutual respect and great communication make the journey fun and enjoyable so that the next generation can continue to grow and truly build on stepping stones eked out by the hard graft of their predecessors.